Isaiah 7:14 Interpretation Timeline: “Maiden” vs. “Virgin.”

Matthew 1:23 in most translations today read that a virgin (Mary) will conceive and give birth to a son who will be called Immanuel and references the prophesy at Isaiah 7:14. However, the original Hebrew wording of Isaiah 7:14 doesn’t use the word “virgin” but “young maiden.” So, which is it or is it both? By referencing some of the oldest sources, this paper attempts the reader to make an informed decision:

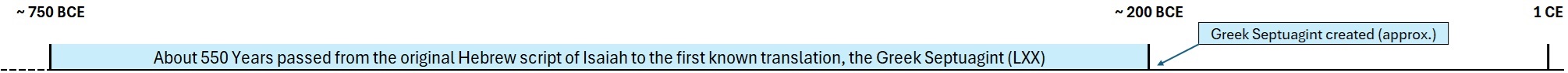

About 550 Years passed from the original Hebrew script of Isaiah (~750 BCE) to the first known translation, the Greek Septuagint (LXX ~200 BCE) which mistranslated the Hebrew word for maiden as virgin. The original meaning in Hebrew at Isaiah 7:14 meant a young maiden would give birth. There’s no indication or hint of some type of miraculous birth. This was Trypho’s argument with Justin Martyr in 155 CE in the Dialog with Trypho. Trypho was a Jew and took the side of the original Hebrew meaning which could be easily seen by looking at the context of Isaiah 7: This was that the young maiden would give birth, and his name would be called Immanuel. Before the boy knew how to reject bad and choose good, the kings who terrified king Ahaz (Who Isaiah was talking to), would be no longer a threat (Isaiah 7:14-16). Trypho argued that Justin was looking for unjustified passages to glorify Jesus. However, Justin sided with the mistranslation of the Greek Septuagint which renders the Hebrew word for “young maiden” as “virgin.”

The Hebrew words for young maiden and virgin are very different. A good example to compare with Isaiah 7:14 is in Genesis 24:16 (RSVCE): “The maiden was very fair to look upon, a virgin (Heb., betulah), whom no man had known.” Comments: The Hebrew term used in Genesis 24:16 to describe Rebekah as a young woman is בְּתוּלָה (betulah). This word typically denotes a young woman, often with an implication of virginity, but its exact meaning can vary slightly depending on the context. In this specific verse, betulah is paired with the phrase “no man had known her”, which clarifies her virginity, as betulah alone does not always exclusively mean “virgin” without additional context.

Comments of Isaiah 7:14: The original Hebrew word in Isaiah 7:14 that is often mistranslated as “virgin” is עַלְמָה (almah). This term generally means “young woman” or “maiden,” typically of marriageable age, but it does not specifically imply virginity. To imply a miraculous virgin birth is adding an incorrect meaning to the original text. It is embellishing the original text which is being used to support the Greek version of Matthew 1:23.

The Book of Isaiah is estimated to have been written around the 8th century BCE, likely between 740 and 700 BCE. The first known translation of Isaiah, part of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures), is believed to have been completed around the 3rd century BCE, possibly between 300 and 200 BCE. This places approximately 500 to 600 years between the original Hebrew text and its first known translation into Greek.

This significant time gap highlights how later interpretations—such as the translation of almah in Isaiah 7:14 to parthenos (“virgin”)—reflect the beliefs and theological frameworks of the translators’ era, which differed from the original context of Isaiah.

Here are the approximate dates for each of the early church commentators’ statements regarding the Hebrew origins of the Gospel of Matthew:

1. Papias of Hierapolis: Papias’s writings, which mention Matthew’s Gospel being written in Hebrew, are dated to around 100–130 CE. His work, Expositions of the Sayings of the Lord, is lost, but this comment is preserved by Eusebius in the 4th century.

2. Irenaeus of Lyons: Irenaeus wrote Against Heresies, which includes his comments on the origins of Matthew’s Gospel, around 180 CE.

3. Origen of Alexandria: Origen’s comments on Matthew’s Gospel were likely written in the early to mid-3rd century, around 225–250 CE. Eusebius preserved Origen’s statements in his Ecclesiastical History.

4. Eusebius of Caesarea: Eusebius wrote Ecclesiastical History, which references Papias, Origen, and others on the Hebrew origins of Matthew, around early 4th century CE (specifically c. 313–325 CE).

5. Epiphanius of Salamis: Epiphanius wrote Panarion, which discusses the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew as used by the Nazarenes, around 374–377 CE.

6. Jerome: Jerome made multiple statements regarding the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew, including his prefaces and letters. His comments on seeing a Hebrew version were written between 382–420 CE.

7. Clement of Alexandria: Clement’s writings, such as Stromata, which touch on the Jewish character of Matthew’s Gospel, were composed around 200 CE.

These statements, spanning from the early 2nd century to the early 5th century, reflect a consistent tradition within the early church regarding a Hebrew or Aramaic origin for the Gospel of Matthew.

Papias of Hierapolis (c. 60–130 CE)

• Papias, an early church father, is one of the earliest sources to mention that Matthew’s Gospel was originally written in Hebrew. He reportedly wrote: “Matthew collected the oracles [sayings] in the Hebrew dialect, and each one interpreted them as best he could.”

• This statement is preserved in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History (Book 3, Chapter 39), and suggests that an original Hebrew or Aramaic version of Matthew existed, which was later translated into Greek.

Irenaeus of Lyons, in his work Against Heresies (written around 180 CE), specifically comments on the origins of the Gospel of Matthew. He states that:

“Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome and laying the foundations of the Church.”

This statement suggests several key points:

1. Hebrew or Aramaic Origins: Irenaeus claims that Matthew wrote his Gospel “among the Hebrews in their own dialect,” which many scholars interpret to mean it was originally composed in Hebrew or Aramaic, languages spoken by Jewish people of that time.

2. Timing and Audience: Irenaeus associates the writing of Matthew’s Gospel with the period when Peter and Paul were active in Rome. This would place its writing in the apostolic era, likely before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE. Irenaeus implies that Matthew’s Gospel was intended for a primarily Jewish-Christian audience, reinforcing the idea that it would be written in a language accessible to them.

3. Missionary Context: Irenaeus sees the composition of Matthew’s Gospel as part of the early Christian missionary activity, intended to document Jesus’ teachings for the Hebrew-speaking members of the community.

This statement by Irenaeus supports the early church tradition that Matthew’s Gospel was initially composed for Jewish believers and written in a Hebrew or Aramaic dialect before being translated into Greek for a broader audience.

Matthew wrote the gospel of Matthew most likely before Rome destroyed the temple in 70 CE, given the apparent freedom that Paul and Peter had in Rome to help establish the church there.

Irenaeus also comments on groups that denied fundamental aspects of orthodox Christian belief, including the virgin birth.

Origen of Alexandria (c. 184–253 CE), one of the early Christian scholars and theologians, commented on the original language and audience of the Gospel of Matthew. His remarks, preserved by Eusebius of Caesarea in Ecclesiastical History (Book 6, Chapter 25), suggest that Matthew’s Gospel was written specifically for a Hebrew-speaking Jewish-Christian audience. Origen states:

“As having learned by tradition concerning the four Gospels, which alone are undisputed in the Church of God under heaven, that the first written was that according to Matthew, who was once a tax collector, but afterwards an apostle of Jesus Christ, who published it for those who had come to faith from Judaism, composed as it was in the Hebrew language.”

In summary, Origen’s comments highlight several points:

1. Authorship by Matthew: Origen affirms that Matthew, one of Jesus’ apostles and a former tax collector, was the author of this Gospel.

2. Written in Hebrew: Origen states that Matthew’s Gospel was originally written “in the Hebrew language” (which may also refer to Aramaic, as the terms were sometimes used interchangeably in the early church). This implies that the Gospel was intended for a Jewish audience who spoke Hebrew or Aramaic.

3. Audience of Jewish Converts: Origen notes that Matthew’s Gospel was published “for those who had come to faith from Judaism,” meaning Jewish converts to Christianity. This aligns with the view that Matthew’s Gospel was especially focused on connecting Jesus’ life and teachings with Jewish prophecy and tradition.

Origen’s comments reinforce the early church tradition that Matthew’s Gospel was initially composed in Hebrew or Aramaic before being translated into Greek for wider distribution. His emphasis on its original Hebrew composition underscores the Gospel’s connection to Jewish-Christian roots.

Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260–340 CE), a prominent early church historian, discussed the origin of the Gospel of Matthew in his work Ecclesiastical History (Book 3, Chapter 24).

Eusebius cites earlier traditions, particularly the writings of Papias of Hierapolis, to provide an account of Matthew’s Gospel. Here’s what Eusebius states:

Matthew’s Gospel Written in Hebrew

Eusebius writes that:

“Matthew had first preached to Hebrews, and when he was about to go to others, he committed his Gospel to writing in his native tongue, and thus compensated for the loss of his presence to those he was leaving.”

This statement reflects the belief that:

1. Matthew Wrote in Hebrew: Eusebius reports the tradition that Matthew initially wrote his Gospel in Hebrew or Aramaic, the language of the Jewish people at the time.

2. For a Jewish Audience: Matthew’s Gospel was tailored to Jewish Christians, emphasizing the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies to establish Jesus as the Messiah.

Citing Papias

Eusebius credits Papias of Hierapolis, an early 2nd-century church father, with this tradition. Papias had written that:

“Matthew composed the oracles [or sayings] in the Hebrew dialect, and each one interpreted them as he could.”

This indicates that the Hebrew Gospel was likely translated into Greek by others, which may explain the differences between early versions of Matthew.

Greek Version of Matthew

Eusebius does not dismiss the canonical Greek Gospel of Matthew but acknowledges that it was widely used in his time. He attributes the Greek version to a translation or adaptations of Matthew’s original Hebrew text.

Summary of Eusebius’ View:

1. Matthew’s Gospel originated in Hebrew or Aramaic, written for Jewish Christians.

2. It was later translated into Greek, which became the form widely circulated in the early Church.

3. Eusebius emphasizes that this tradition aligns with earlier accounts, such as those by Papias, confirming a long-held belief in the Hebrew origins of Matthew’s Gospel.

Eusebius’ account underscores the early Church’s acknowledgment of Matthew’s Gospel as deeply rooted in Jewish-Christian tradition while affirming its role as one of the four canonical Gospels.

Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403 CE), an early church father and bishop, discussed the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew in his work Panarion, a comprehensive treatise on heresies. Epiphanius mentions that a Hebrew version of Matthew was used by certain Jewish-Christian groups, particularly the Nazarenes and Ebionites. Here’s what he conveyed about the Hebrew Matthew:

1. Gospel of the Nazarenes:

Epiphanius noted that the Nazarenes, a Jewish-Christian sect, had a version of the Gospel of Matthew written in Hebrew. He referred to this text as the “Gospel according to the Hebrews” or “Gospel of the Nazarenes.” He described the Nazarenes as adhering to Jewish customs while recognizing Jesus as the Messiah, and they used this Hebrew version of Matthew in their worship and teachings.

2. Ebionite Use of a Hebrew Gospel:

Epiphanius also reported that the Ebionites, another Jewish-Christian sect, used a version of Matthew’s Gospel in Hebrew, although he indicated that their version was “altered” to fit their theological views (e.g., a denial of the virgin birth). The Ebionites’ version was likely different from the canonical Greek Gospel of Matthew, as they modified it to align with their beliefs. However, this view must include the possibility that what he viewed as canonical, deemed by the church, was in fact incorrect and written later than the original.

3. Details on Language and Origin:

Epiphanius asserted that Matthew originally wrote his Gospel in Hebrew for a Jewish audience. He believed that this Hebrew version continued to circulate among certain Jewish-Christian communities even after the Greek translations were widely adopted by the early church.

Epiphanius’ comments support the early church tradition that Matthew’s Gospel was first composed in Hebrew. He observed that this Hebrew version persisted within certain Jewish-Christian communities, even as the Greek text became more common in mainstream Christianity. Epiphanius viewed the Hebrew Matthew as a significant but somewhat distinct version of the Gospel that reflected the beliefs and practices of these early Jewish followers of Jesus.

Jerome began composing the Vulgate, his Latin translation of the Bible, around 382 CE, following a commission from Pope Damasus I. However, his engagement with the original Gospel of Matthew in Hebrew appears to have occurred later, after he had already made significant progress on the Vulgate.

Timeline and Context:

1. The Start of the Vulgate Project:

Jerome began with the Gospels, translating them from Greek into Latin, as the primary goal was to produce a standardized and accurate Latin Bible for the Western Church. This work was based on the Greek texts of the Gospels and not the Hebrew or Aramaic originals.

2. Encounter with the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew:

Jerome, later in his career, claimed to have seen and even translated portions of a Hebrew version of the Gospel of Matthew, which he associated with the Nazarenes or Ebionites. He discusses this in several of his writings, such as his Commentary on Matthew and in letters like Letter 75 to Pope Damasus.

In these writings, Jerome identifies the Hebrew Matthew as distinct from the canonical Greek text, suggesting it was an early tradition used by Jewish Christians. However, there is no evidence that he used this text extensively in composing the Vulgate.

3. Timing and Influence:

Jerome’s encounter with the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew seems to have occurred while he was living in Bethlehem (from 386 CE onward). By this time, much of his Vulgate work was already complete, including the Latin translation of the Gospels. Therefore, Jerome likely did not consult the Hebrew Matthew in the initial composition of the Vulgate, as his earlier work was primarily based on Greek manuscripts and the Septuagint (for the Old Testament).

Conclusion:

Jerome composed the Vulgate largely using Greek sources for the Gospels and the Septuagint for parts of the Old Testament. While he later encountered a Hebrew version of Matthew, it does not appear that this influenced the composition of the Vulgate, as his engagement with the Hebrew text came after much of his work on the Latin Bible had been completed.

Jerome’s Observations on Differences Between the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew and the Canonical Greek Version

Introduction

Jerome (c. 347–420 AD), a prominent Church Father and biblical scholar, is best known for translating the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate). He was deeply interested in the origins of the Gospel texts and believed that the Apostle Matthew originally wrote his Gospel in Hebrew (or Aramaic) for the Jewish Christians in Palestine. Jerome claimed to have accessed this Hebrew version, particularly the one used by the Nazarenes, a Jewish-Christian sect. In his writings, Jerome mentioned several differences between this Hebrew Gospel and the canonical Greek Gospel of Matthew used in his day.

Key Differences Noted by Jerome

1. Omission of the Genealogy and Birth Narratives

Observation: Jerome noted that the Hebrew Gospel used by the Nazarenes did not contain the genealogy of Jesus or the account of His birth from the Virgin Mary, which are present in the first two chapters of what the church deems as the “canonical” Gospel of Matthew, written in Greek.

Quote: In his commentary on Matthew, Jerome writes:

“In the Gospel which the Nazarenes and Ebionites use, which I recently translated into Greek from Hebrew, and which most people call the authentic Gospel of Matthew, it lacks the genealogies at the beginning and the narratives of the birth.”

Significance: The absence of these sections suggests a different theological emphasis, possibly reflecting the beliefs of the Nazarene community, which had different views on the virgin birth and the Davidic lineage of Jesus.

2. Additional Details in Miracle Accounts

Observation: Jerome mentioned that certain miracle stories in the Hebrew Gospel included details not found in the Greek version.

Example: In the healing of the man with the withered hand (Matthew 12:9–13), the Hebrew Gospel adds that the man was a mason who sought healing to avoid begging for food.

Quote: Jerome writes:

“In the Gospel which the Nazarenes use, we find the man with the withered hand described as a mason who sought help in these words: ‘I was a mason seeking a livelihood with my hands; I beseech you, Jesus, to restore me to health, so that I may not have to beg for food in shame.'”

Significance: This addition provides more context to the miracle and highlights Jesus’ compassion for those in need.

3. Variations in the Lord’s Prayer

Observation: Jerome observed differences in the wording of the Lord’s Prayer in the Hebrew Gospel.

Quote: In his commentary on Matthew 6:11, he notes:

“In the Gospel according to the Hebrews, instead of ‘Give us this day our daily bread,’ we find ‘Give us today our bread for tomorrow.'”

Significance: This variation could reflect different theological interpretations of dependence on God and the nature of spiritual sustenance.

4. Unique Sayings of Jesus

Observation: The Hebrew Gospel contained sayings of Jesus not present in the canonical Gospels.

Example: Jerome mentions a passage where Jesus refers to the Holy Spirit as his mother.

Quote: In his Commentary on Micah, Jerome writes:

“In the Gospel which the Nazarenes read, we find: ‘And just now, my mother, the Holy Spirit, took me by one of my hairs and carried me to the great mountain Tabor.'”

Significance: This saying reflects a different theological perspective and shows the diversity of early Christian traditions.

5. Different Post-Resurrection Appearances

Observation: Jerome noted that the Hebrew Gospel included accounts of post-resurrection appearances not found in the canonical Matthew.

Quote: In “De Viris Illustribus” (On Illustrious Men), he writes:

“Also, the Gospel called according to the Hebrews, recently translated by me into Greek and Latin, which Origen often uses, records after the resurrection of the Savior: ‘Now the Lord, when he had given the linen cloth to the servant of the priest, went to James and appeared to him.'”

Significance: This emphasizes the role of James, the brother of Jesus, in the early Church.

6. Variations in Scriptural Quotations

Observation: Jerome observed that the Hebrew Gospel sometimes quoted Old Testament scriptures differently.

Example: In Matthew 2:23, the canonical Gospel says, “He shall be called a Nazarene,” but Jerome notes that the Hebrew Gospel might have had a different reference.

Significance: Different scriptural quotations could reflect variations in textual traditions or theological emphases.

7. Alternate Accounts of Baptism

Observation: Jerome mentions variations in the account of Jesus’ baptism.

Quote: In his commentary, he notes:

“In the Gospel according to the Hebrews, which the Nazarenes use, at the time of the baptism, the whole fount of the Holy Spirit descended and rested upon him.”

Significance: This emphasizes the descent of the Holy Spirit in a way that may differ from the canonical accounts.

Jerome’s Reflections on These Differences

• Authenticity and Authority: While Jerome referred to the Hebrew Gospel as the “authentic Gospel of Matthew,” he recognized that it differed from the Greek version used by the wider Church. He grappled with the question of which version should be considered authoritative.

• Purpose of Translation: Jerome translated the Hebrew Gospel into Greek and Latin to make it accessible and to better understand the origins of the Gospel narratives.

• Scholarly Interest: His interest in the Hebrew Gospel reflects a scholarly desire to explore the earliest Christian texts and to engage with different Christian communities.

Conclusion

Jerome noted several differences between the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew used by the Nazarenes and the canonical Greek Gospel of his day, including:

• Omission of the genealogy and birth narratives.

• Additional details in miracle stories, providing more context to Jesus’ actions.

• Variations in familiar passages like the Lord’s Prayer, reflecting different interpretations.

• Unique sayings and accounts, highlighting the diversity of early Christian traditions.

Jerome’s observations contribute to our understanding of the textual variations and theological diversity in early Christianity. His work underscores the complexities involved in the transmission and preservation of the Gospel texts.

Additional information:

To create a well-supported theological argument that both Joseph and Mary were the biological parents of Jesus, we’ll explore the prophecy in Isaiah 7:14, historical context, linguistic analysis, and scriptural patterns regarding children in Isaiah’s prophecies. This approach will give a nuanced view of Isaiah’s text and how early audiences might have understood it without the later doctrine of the virgin birth. Here’s a structured approach with arguments:

1. Original Reading of Isaiah 7:14 from the Dead Sea Scrolls

Textual Insights: The Dead Sea Scrolls provide some of the oldest extant manuscripts of the Hebrew Scriptures, including Isaiah. In the Great Isaiah Scroll, Isaiah 7:14 reads similarly to the Masoretic Text: “Behold, the young woman (Hebrew: almah) shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel.” The word almah here has historically meant “young woman” rather than “virgin.”

Interpretation Implication: The translation of almah as “virgin” is a later interpretive addition found primarily in the Greek Septuagint (parthenos), while the original Hebrew conveys a more general notion of a young woman, not necessarily implying virginity. This leaves room for a reading that Joseph and Mary could be biological parents without challenging Isaiah’s prophecy, if one assumes Isaiah 7:14 is associated with the birth of Jesus.

2. Date of Original Composition and Context of Isaiah’s Prophecies

Historical Context: Scholars generally date the book of Isaiah to around the 8th century BCE, during a period of crisis for the Kingdom of Judah. The prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 originally addresses King Ahaz amid a geopolitical struggle, giving assurance through a child symbolizing God’s presence (“Immanuel”).

Contemporary Meaning: In the 8th century BCE, prophecy was often symbolic and timely, focused on immediate deliverance rather than distant events. Thus, Isaiah’s audience likely understood the prophecy as relevant to Ahaz’s time, supporting the idea that it may refer to a natural conception rather than a miraculous birth.

3. Isaiah’s Use of Children in Prophecy

Pattern of Child-Symbolism: Isaiah frequently uses children symbolically in his prophecies to communicate God’s intentions and promises.

Isaiah 7:3: Isaiah’s own son, Shear-Jashub, serves as a symbolic reassurance to King Ahaz of a remnant returning.

Isaiah 8:3-4: Another son, Maher-Shalal-Hash-Baz, symbolizes the imminent plundering of Syria and Israel, marking God’s intervention in historical events.

Immanuel as Symbolic Child: In this pattern, Isaiah 7:14’s Immanuel could similarly be interpreted as a symbolic figure meant to signify God’s favor rather than as an individual marked by miraculous conception. The consistent theme of children as signs in Isaiah supports the interpretation of Jesus as the biological child of Mary and Joseph, adhering to Isaiah’s symbolic framework.

4. Original Understanding of Isaiah 7:14 and the Meaning of Almah

The Term Almah: In Hebrew, almah typically denotes a young woman of marriageable age without explicit implication of virginity. Hebrew culture had specific terms for virginity, like betulah, which is absent here. The choice of almah would suggest a straightforward meaning—a young woman, likely a future wife and mother, who will conceive a child in the usual manner.

Original Audience Understanding: In Isaiah’s context, the sign to Ahaz would not have implied a miraculous conception. Instead, it communicated a broader divine assurance: that within a generation (the birth and maturation of a child), God’s deliverance would be realized. This does not necessitate a virgin birth, leaving room for the view that Jesus, as Immanuel, could be born from two natural parents, Joseph and Mary.

5. Additional Linguistic and Theological Considerations

Septuagint Translation Influence: The Septuagint, the Greek translation of Hebrew Scriptures used by early Christians, rendered almah as parthenos (“virgin”), shaping early Christian interpretation. However, the Septuagint’s interpretive choices don’t always reflect Hebrew text meanings. By focusing on the original Hebrew, a biological parentage for Jesus fits within Isaiah’s intended message.

Theological Coherence: Viewing both Joseph and Mary as biological parents aligns with the humanity of Jesus emphasized in several New Testament accounts (e.g., his genealogy in Matthew and Luke). It presents Jesus as fully human and subject to the lineage of David through Joseph, fulfilling Messianic prophecies without requiring virgin birth doctrine.

Summary Argument

Based on the oldest textual evidence (Dead Sea Scrolls) and historical-linguistic analysis, Isaiah 7:14 originally conveyed a prophecy of hope through a natural conception. This would align with Isaiah’s consistent use of children symbolizing divine action in immediate circumstances. The term almah in the original Hebrew supports a reading of “young woman” without the miraculous implications later attributed to it. Consequently, early readers, viewing Jesus as a fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy, could regard Joseph and Mary as his biological parents without detracting from his Messianic role, embracing the full humanity that aligns with Jesus’ genealogical inclusion in David’s line.

More on Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho:

The earliest known written argument outside of Matthew and Luke that connects Isaiah 7:14 with the concept of a virgin birth and Jesus’ identity appears in the works of Justin Martyr, a 2nd-century Christian apologist. In his dialogue Dialogue with Trypho, written around 155-160 CE, Justin Martyr explicitly interprets Isaiah 7:14 as a prophecy of the virgin birth of Jesus. He argues that this prophecy is fulfilled uniquely in Jesus, emphasizing the parthenos (virgin) reading from the Septuagint, which he sees as essential to proving Jesus’ divine origin and messianic role.

Justin’s work is significant because it represents one of the first known extended theological arguments that associates Isaiah 7:14 with the virgin birth outside of the Gospels, positioning the prophecy as a foundational claim for early Christian doctrine on Jesus’ miraculous birth and divinity.

Justin Martyr’s arguments for a virgin birth in Dialogue with Trypho are rooted in both prophetic interpretation and theological reasoning. Here’s a summary of his main points:

1. Isaiah 7:14 as Prophecy: Justin emphasizes Isaiah 7:14, interpreting almah (translated as parthenos in the Septuagint) to mean “virgin.” He argues that this was a deliberate and divinely inspired prophecy that could only be fulfilled by Jesus. He points out that a “young woman” giving birth would not be miraculous or remarkable, but a virgin birth would be an extraordinary sign, fitting the prophecy’s divine nature.

2. Contrast with Human Expectations: Justin argues that the virgin birth sets Jesus apart from any other figure because it underscores His divine origin. He reasons that if Jesus had been conceived through ordinary means, He would not fulfill the prophecy of a miraculous sign intended to demonstrate God’s direct intervention in human affairs.

3. Typology and Fulfillment of Prophecy: Justin presents a typological reading, linking events and figures in the Hebrew Scriptures with New Testament events. He argues that Jesus is the ultimate fulfillment of many Old Testament prophecies, and the virgin birth is essential to this role. For instance, he draws parallels between Jesus and figures like Isaac, whose birth was also promised by God, though not virgin-born, to indicate a pattern of divine intervention.

4. Defense against Jewish Interpretations: In his dialogue with Trypho (representing a Jewish perspective), Justin defends the Christian interpretation against Jewish objections that Isaiah 7:14 refers only to a young woman (without implying virginity) and was fulfilled in a contemporary historical context. He asserts that Isaiah’s words were meant to point forward to the Messiah in a unique and supernatural way, not merely to a young woman’s natural conception.

5. Supernatural Nature of Christ: Justin uses the virgin birth to underscore Jesus’ divinity, positing that being born of a virgin aligns with Jesus’ unique nature as the Son of God. This divine origin is central to his mission and the salvific work Justin believes Jesus was sent to accomplish.

Justin Martyr’s defense of the virgin birth thus hinges on his interpretation of Isaiah as a prophecy intended to herald the Messiah’s supernatural entry into the world, fulfilled uniquely in Jesus and providing proof of God’s intervention and fulfillment of messianic promises.

In Dialogue with Trypho, Trypho (representing a Jewish perspective) raises several arguments against Justin Martyr’s interpretation of Isaiah 7:14 as a prophecy of a virgin birth. These arguments reflect Jewish understandings of the prophecy and aim to challenge the Christian claim of Jesus’ divine origin through a miraculous birth. Here are Trypho’s main points:

1. Interpretation of Almah: Trypho argues that the Hebrew word almah in Isaiah 7:14 simply means “young woman” rather than “virgin.” He suggests that almah does not necessarily imply virginity and points out that Hebrew has a specific word for “virgin,” betulah, which Isaiah does not use here. From Trypho’s perspective, the choice of almah indicates that the prophecy refers to a naturally conceived child from a young woman, not a miraculous virgin birth.

2. Immediate Historical Context of the Prophecy: Trypho asserts that Isaiah’s prophecy in chapter 7 was intended for King Ahaz and related to the political and military threats facing Judah at the time. In this interpretation, the child Immanuel is meant as a contemporary sign to Ahaz, showing that within the child’s lifetime, God would deliver Judah from its enemies. This understanding implies that the prophecy was fulfilled shortly after it was given, not hundreds of years later in the figure of Jesus.

3. Lack of a Need for a Miraculous Sign in the Original Context: Trypho argues that Isaiah 7:14 does not imply a miraculous event, such as a virgin birth. Instead, he sees the prophecy as a symbol of hope and divine protection for Judah in a critical historical moment. He suggests that a natural birth from a young woman could still serve as a sign, especially if the child is named “Immanuel,” signifying “God with us” as a reminder of divine presence, without requiring a miraculous conception.

4. Jewish Messianic Expectations: Trypho contends that the Jewish understanding of the Messiah does not necessitate a virgin birth. Jewish messianic expectations were rooted in an earthly king who would come from David’s line, through natural means, and serve as a liberator for Israel. From Trypho’s perspective, Jesus does not fit these criteria, and therefore, Isaiah 7:14 cannot be referring to him.

5. Disagreement with Christian Typology: Trypho challenges Justin’s typological approach, where events or people in the Hebrew Scriptures are seen as foreshadowing Christ. He argues that Christians are misappropriating Jewish texts, forcing them to fit Christian narratives. Trypho’s objection here is that Justin’s interpretation reads Jesus into passages that, in the Jewish view, were not meant to refer to the Messiah or a future miraculous birth.

These points reflect Trypho’s broader argument that the Christian interpretation of Isaiah 7:14 as a virgin birth prophecy is a departure from the original text and Jewish tradition. He sees the prophecy as focused on the immediate historical context and views the term almah as supporting a natural, rather than miraculous, conception.

Isaiah prophesying to king Ahaz (Isaiah 7)

Isaiah 7:1-16 (ERV):

7 Ahaz was the son of Jotham, who was the son of Uzziah. Rezin was the king of Aram, Pekah son of Remaliah[a] was the king of Israel. When Ahaz was king of Judah, Rezin and Pekah went up to Jerusalem to attack it, but they were not able to defeat the city.[b]

2 The family of David received a message that said, “The armies of Aram and Ephraim have joined together in one camp.” When King Ahaz heard this message, he and the people became frightened. They shook with fear like trees of the forest blowing in the wind.

3 Then the Lord told Isaiah, “You and your son Shear Jashub[c] should go out and talk to Ahaz. Go to the place where the water flows into the Upper Pool,[d] on the street that leads up to Laundryman’s Field.

4 “Tell Ahaz, ‘Be careful, but be calm. Don’t be afraid. Don’t let those two men, Rezin and Remaliah’s son,[e] frighten you! They are like two burning sticks. They might be hot now, but soon they will be nothing but smoke. Rezin, Aram, and Remaliah’s son became angry 5 and made plans against you. They said, 6 “Let’s go fight against Judah and divide it among ourselves. Then we will make Tabeel’s son the new king of Judah.”’”

7 But the Lord God says, “Their plan will not succeed. It will not happen 8 because Aram depends on its capital Damascus, and Damascus is led by its weak king Rezin. And don’t worry about Ephraim. Within 65 years it will be crushed, no longer a nation. 9 Ephraim depends on its capital Samaria, and Samaria is led by Remaliah’s son. So you have no reason to fear. Believe this, or you will not survive.”

10 Then the Lord spoke to Ahaz again 11 and said, “Ask for a sign from the Lord your God to prove to yourself that this is true. You can ask for any sign you want. The sign can come from a place as deep as Sheol[f] or as high as the skies.[g]”

12 But Ahaz said, “I will not ask for a sign as proof. I will not test the Lord.”

13 Then Isaiah said, “Family of David, listen very carefully! Is it not enough that you would test the patience of humans? Will you now test the patience of my God? 14 But the Lord will still show you this sign:

The young woman is pregnant[h]

and will give birth to a son.

She will name him Immanuel.[i]

15 He will eat milk curds and honey[j]

as he learns to choose good and refuse evil.

16 But before he is old enough to make that choice,

the land of the two kings you fear will be empty.

Below is a revised and expanded explanation that integrates previous points and includes a discussion about the implications of Isaiah 7:14’s translation in a hypothetical original Hebrew version of Matthew’s Gospel:

1. Early Church Traditions About a Hebrew Matthew

Multiple early Church Fathers attested to the idea that the Apostle Matthew originally composed his Gospel in Hebrew (or Aramaic) for a community of Jewish believers:

• Papias (c. 60–130 AD): Quoted by Eusebius, Papias claimed Matthew compiled the “oracles” of Jesus in the Hebrew language.

• Irenaeus (c. 130–202 AD) and Origen (c. 184–253 AD): Both reaffirmed that Matthew was first written for Jewish Christians in their own language, likely Hebrew or Aramaic.

• Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260–339 AD): Recorded the tradition that Matthew wrote his Gospel in Hebrew before leaving to preach elsewhere.

• Jerome (c. 347–420 AD): Not only reiterated this tradition but claimed to have seen a Hebrew Gospel of Matthew used by Jewish-Christian groups (Nazarenes and Ebionites).

While these sources do not fully agree on the exact nature of this Hebrew text, they create a strong patristic witness that something akin to a Hebrew Matthew circulated early on.

2. Jewish-Christian Texts Without the Virgin Birth Narrative

Certain early Christian sects, notably the Nazarenes and Ebionites, reputedly used a Hebrew Gospel that differed from the canonical Greek Gospel of Matthew. According to Jerome and Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403 AD):

• Epiphanius (Panarion): The Ebionites had a Gospel of Matthew in Hebrew, but it lacked the opening chapters that detail the virgin birth and genealogies. Instead, their Gospel started from Jesus’ baptism, omitting any suggestion of a miraculous conception.

• Jerome: Mentioned that the Nazarenes’ Hebrew Gospel lacked the infancy narratives and genealogies as found in the canonical text.

This strongly suggests that at least some Jewish-Christian groups possessed a version of Matthew without the virgin birth narrative. Whether this represents an “original” form is debatable, but it underscores that not all early Matthew traditions included the virgin birth story as we have it today.

3. Theological and Historical Context

• Jewish-Christian Emphasis: Groups like the Nazarenes and Ebionites tended to preserve Jewish practices and considered Jesus a Messiah figure closely tied to Jewish law. A Gospel without the virgin birth narrative and genealogical claims might reflect a theological stance where Jesus was a human prophet or Messiah chosen by God, rather than pre-existent and miraculously conceived.

• Textual Diversity in the Early Church: In the first two centuries, local Christian communities may have preserved, transmitted, and adapted Gospel texts in line with their theological outlooks. Such an environment allowed for the coexistence of different versions of a given Gospel tradition—some more developed theologically (including miraculous birth stories), others more primitive or aligned with a lower Christology.

4. The Isaiah 7:14 Question: “Virgin” vs. “Maiden”

One key piece of evidence in the canonical Greek Matthew’s account of Jesus’ birth is the citation of Isaiah 7:14:

Canonical Matthew (1:23) quotes the Greek Septuagint:

“Behold, the virgin (Greek: parthenos) shall conceive and bear a son…”

The Hebrew text of Isaiah 7:14 uses the word ‘almah, typically meaning “young woman,” not necessarily “virgin.” The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, rendered ‘almah as parthenos, meaning “virgin,” and this became foundational for the theological interpretation of Jesus’ birth as miraculous.

• If the Original Was Hebrew: If an early Hebrew version of Matthew existed, it would have been less likely to rely on the Greek Septuagint’s translation of Isaiah 7:14. Instead, it could have cited or alluded to the Hebrew text itself, which says “young woman” (almah). This nuance would have significantly affected the theological claim. A Hebrew source using the native term ‘almah’ might not naturally yield a “virgin birth” narrative unless the author deliberately interpreted or adapted the verse to support that theology.

• Implications for the Virgin Birth Narrative:

If the original Hebrew Matthew did not contain the infancy narratives, it also would not need to rely on Isaiah 7:14’s “virgin” reading to bolster its claims. Without a virgin birth story, citing the Hebrew text with a neutral “young woman” would not contradict the Gospel’s message—if its Christology did not hinge on a miraculous conception. In fact, a Hebrew Matthew aligned with a Jewish-Christian community that rejected or minimized the virgin birth would more likely avoid the Septuagint’s “virgin” mistranslation and either omit the infancy material entirely or present a reading more faithful to the Hebrew scriptures. Thus, the Hebrew Gospel would have logically quoted the Hebrew Isaiah, preserving the ambiguity of “young woman” rather than imposing the Greek “virgin” reading.

5. Scholarly Considerations and Plausibility

Modern historical-critical scholarship often notes that the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke show signs of later theological development. The idea of Jesus’ miraculous conception by the Holy Spirit and explicit use of Isaiah 7:14 via the Septuagint’s translation is part of a theological shaping of Jesus’ story to highlight his divine origin. If an early Hebrew Matthew focused on Jesus’ teachings, life, death, and resurrection without this theological lens, it would not have sought scriptural support for a virgin birth. Instead, it might have presented Jesus as a messianic figure within a Jewish interpretive framework, using the Hebrew Bible as understood by contemporaneous Jewish believers.

6. Conclusion

The plausibility that an original Gospel of Matthew was written in Hebrew and did not support the virgin birth narrative arises from several converging lines of evidence and reasoning:

1. Patristic Testimony: Early Christian writers (Papias, Jerome, Epiphanius) acknowledged a Hebrew Matthew or Matthew-like Gospel.

2. Jewish-Christian Variants: Known communities like the Ebionites and Nazarenes used Hebrew Gospel traditions lacking the virgin birth and genealogical material.

3. Theological Fit: A community less invested in a divine pre-existence or miraculous conception of Jesus would logically maintain a Gospel without those narratives.

4. Textual and Linguistic Evidence: A Hebrew original would not rely on the Septuagint’s “virgin” translation of Isaiah 7:14. Without that cornerstone of miraculous birth prophecy, the impetus for including a virgin birth narrative would be diminished.

While we cannot be certain that the canonical Matthew directly evolved from a non-virgin-birth Hebrew predecessor, the existence of variant early Christian texts and the testimonies of the Church Fathers make it a plausible historical scenario. It underscores the richness and diversity of early Christian textual traditions and the ways theological emphases shaped the Gospels as we know them.

Even if Jesus was born of and through Joseph and Mary, this would not make his role as mankind’s savior any less important. Nor would it eliminate his previous role in the heavenly realm. But it would help clarify some scripture and thoughts:

• If Joseph had no biological connection with Jesus, as many think, why does the Greek Matthew, that is widely used today, include the genealogy for Joseph but stops before Jesus?

• If God’s people in ancient times (Hebrews) thought that Isaiah 7:14 indicated that a virgin would give birth to a son to indicate that God was with his people, why weren’t they looking for that either in their day or the future? The virgin would be famous. Mary could have used her status to protect or identify Jesus. But that didn’t happen. There was no reason for anyone to look forward to a miraculous virgin-birth based upon the original Hebrew passage at Isaiah 7:14.

• Why is there no explanation anywhere in the New Testament that Christ was born through a virgin? This is certainly a controversial subject. Much more than circumcision which was debated for over 10 years with much written about it.

• Why wasn’t Jesus named Immanuel? Immanuel is a name not a description. Yet many view it as a description. This gets away from the original Hebrew account at Isaiah 7:14. See names.

• Hebrew was a live language at the time of Christ. John 19:19-20; “Pilate also wrote an inscription and put it on the cross. It read, ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.’ Many of the Jews read this inscription, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city, and it was written in Hebrew, in Latin, and in Greek.”

• Romans 8:3; “For what the law couldn’t do, in that it was weak through the flesh, God did, sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh”

• Second Corinthians 5:21; “For him who knew no sin he made to be sin on our behalf; so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.”

• Hebrews 2:14-18 shows that Christ was obligated to be made like his brothers; “14 Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil— 15 and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. 16 For surely it is not angels he helps, but Abraham’s descendants. 17 For this reason he had to be made like them,[a] fully human in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in service to God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people. 18 Because he himself suffered when he was tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted.”

• Isaiah 53:3: “He was despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows and familiar with suffering.”

• Hebrews 5:1-10 (WEB): For every high priest, being taken from among men, is appointed for men in things pertaining to God, that he may offer both gifts and sacrifices for sins. 2 The high priest can deal gently with those who are ignorant and going astray, because he himself is also surrounded with weakness. 3 Because of this, he must offer sacrifices for sins for the people, as well as for himself. 4 Nobody takes this honor on himself, but he is called by God, just like Aaron was. 5 So also Christ didn’t glorify himself to be made a high priest, but it was he who said to him,

“You are my Son.

Today I have become your father.” Psalm 2:7

6 As he says also in another place,

“You are a priest forever,

after the order of Melchizedek.” Psalm 110:4

7 He, in the days of his flesh, having offered up prayers and petitions with strong crying and tears to him who was able to save him from death, and having been heard for his godly fear, 8 though he was a Son, yet learned obedience by the things which he suffered. 9 Having been made perfect, he became to all of those who obey him the author of eternal salvation, 10 named by God a high priest after the order of Melchizedek.

Other links:

The Sacrifice of Christ (Yeshua/Jesus)

Who is the Son of the Almighty?

Was Jesus (Yahshua/Yeshua) fully human?

Dale Beckman, Jr. Dec. 2024